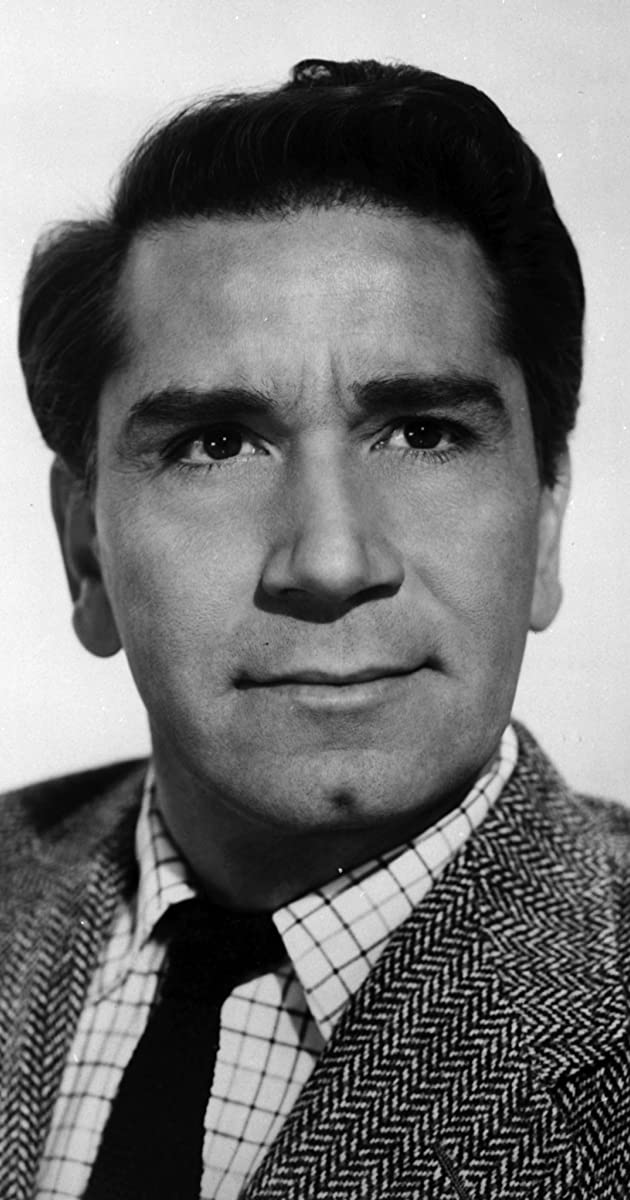

Though his number of film roles amount to a bit over 30, Paul Scofield has cast a giant shadow in the world of stage and film acting. He grew up in West Sussex, the son of a schoolmaster. He attended the Varndean School for Boys in Brighton. The love of acting came early. While still high school age, he began training as an actor at the Croydon Repertory Theatre School (1939) and then at the Mask Theatre School (1940) in London. He took on all the experience he could handle by joining touring companies and also entertained British troops during World War II. He joined the Birmingham Repertory Theatre and, from there in 1946, he moved to Stratford-upon-Avon. There, in the birthplace of William Shakespeare, he had his first great successes. He had the title role in “Henry V”; he was “Cloten” in “Cymbeline”; “Don Adriano de Armado” in “Love’s Labour’s Lost”, “Lucio” in “Measure for Measure”, and then “Hamlet”. And there were many more as he honed himself into one the great Shakespearean actors of the 20th century. With a rich, sonorous voice compared to a Rolls Royce being started up, in one instance, and a great sound rumbling forth from an antique crypt in yet another, he was quickly compared to Laurence Olivier.

Scofield did not move on to commercial theater until 1949, when he took the lead role of “Alexander the Great”, in playwright Terence Rattigan’s unfortunately ill-received “Adventure Story”. And as he continued theater work, he moved toward film very carefully. From his first in 1955, Scofield was always – as with any of his acting assignments – extremely picky about accepting a particular role. It was three years before his second film. Meanwhile, Scofield had the opportunity to play a great lead part in a new play by a schoolmaster-turned-new-playwright, Robert Bolt. The play was “A Man for All Seasons” and Scofield’s choice role was that of “Sir Thomas More”, the great English humanist and chancellor, who defied the ogre “King Henry VIII” in his wish to put aside his first wife for “Anne Bolyne”. It was a once in a lifetime part, and Scofield debuted it in London in 1960. His only appearance on Broadway was the next year in that play, which ran into 1962. It was no surprise that the work began garnering awards for him (see Trivia below for details on theater and film awards).

He returned to Shakespeare in 1962 with Peter Brook, the noted British director and producer, directing him as “Lear” at the newly formed Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) at Stratford. This was a pioneering minimalist production, one of the first “bare stage” efforts – though things were pretty bare stage in Shakespeare’s day. Scofield then did “Coriolanus” and “Love’s Labour’s Lost” for the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Ontario in 1963. His third film came six years after his second screen appearance (1958). This was his standout performance in The Train (1964), a production of his co-star, Burt Lancaster, that grew in size and budget with the entrance of Lancaster’s second choice for director, John Frankenheimer. Some of the difficulties involved might have turned someone of Scofield’s discipline back to the stage thereafter, but the filming of “Seasons” arrived, and he would hardly refuse. With Robert Bolt handling the screenplay and a superlative supporting cast, the film version of A Man for All Seasons (1966) collected some thirty-three international awards, including a three-statue sweep of prime-Oscar categories plus another three for good measure. Scofield was unforgettable as the incisive man of state, able to juggle the volatile politics of the time but always keep his honor and so brimming with faith as to endure the inevitably mounting tide against him.

It suited Scofield for a time to keep his screen-acting to adaptations of plays, books, and ensemble pieces fitted to the big screen. Peter Brook and he teamed again for a film version of the Brook-adapted play Tell Me Lies (1968). The adaptation of Herman Melville’s Bartleby (1970), despite Scofield’s efforts, did not wash as an attempt to update Melville’s story in the late twentieth century. Then Brook was back again to finally attempt what he said had really never been done correctly -adapting Shakespeare to film. Scofield’s 1962 “Lear” was held in high esteem, and Brook decided on a film version, King Lear (1971), an even more uncompromising, even uncomfortable, desolation staging and editing of the tragedy. Despite some oddball camera work and not wholly satisfying adapting of the play, Scofield was magnificent and got his chance to show that he is perhaps the best Lear of modern times. While still keeping a concerted interest in filmed play adaptations, Scofield could be lured into more typical screen drama. He joined former co-star, Burt Lancaster, for the spy thriller, Scorpio (1973), as a memorable Russian comrade of Lancaster from the days of World War II, caught in late-Cold War spy craft brutality.

Through the 1980s, Scofield did a mix of TV and film on both sides of the Atlantic. But he was drawn back to Shakespeare and filming efforts, though in humbler parts, first in the Henry V (1989) of ambitious Kenneth Branagh, as the French king, and, the next year, in the Franco Zeffirelli, Hamlet (1990), as “The Ghost” – with the real buzz being for Mel Gibson as the dour “Prince of Denmark”. Both films were well-crafted with impressive supporting casts. And Scofield could be content that as with all his roles, he was remaining consistent with himself as his own best judge of how to challenge his acting gifts. Gibson was appropriately awed, saying that working with Scofield was like being “thrown into the ring with Mike Tyson” (that is, Mike Tyson then, not now). Through the 1990s, he enjoyed his continued sampling of all acting media, even radio narration and animation voice-over.

The matter of British actors weighing upon the acceptance of knighthoods for their work began most publicly with Scofield. In 1956, after his tour of “Hamlet” with a triumph in Moscow, he gratefully accepted the appointment as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), but thereafter he refused on three occasions the offer of knighthood. “If you want a title, what’s wrong with Mr.? If you have always been that, then why lose your title? “I have a title, which is the same one that I have always had. But it’s not political. I have a CBE, which I accepted very gratefully”. He said this with great simplicity and charm. The matter of ‘theatrical nobility’ has prompted others to follow Scofield’s example. One high profile example with a twist is actor Anthony Hopkins, now an American citizen, who quipped that he only accepted the knighthood because his wife wanted him to do so. In taking the oath of citizenship, Hopkins pledged to “renounce the title of nobility to which I have heretofore belonged”. But Scofield’s demeanor in his logically crafted refusals from the first so fit this man’s very private life. Yet quite averse to being interviewed, he has always been considerate to the public for their patronage. Brilliant man and acting legacy, on and off the stage, Paul Scofield truly is a “Man for All Seasons”.