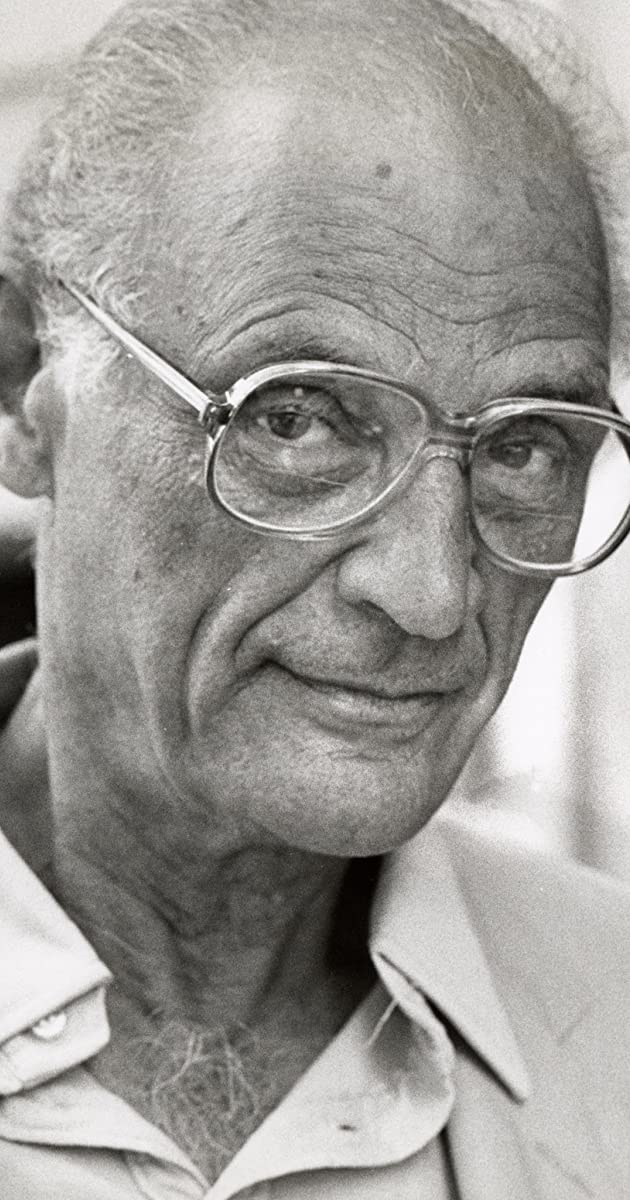

Arthur Asher Miller was born on October 17, 1915, in New York City, one of three children born to Augusta (nee Barnett) and Isidore Miller. His family was of Austrian Jewish descent. His father manufactured women’s coats, but his business was devastated by the Depression, seeding his son’s disillusionment with the American Dream and those blue-sky-seeking Americans who pursued it with both eyes focused on the Grail of Materialism. Due to his father’s strained financial circumstances, Miller had to work for tuition money to attend the University of Michigan, where he wrote his first plays. They were successful, earning him numerous student awards, including the Avery Hopwood Award in Drama for “No Villain” in 1937.

The award was named after one of the most successful playwrights of the 1920s, who simultaneously had five hits on Broadway, the Neil Simon of his day. Now almost forgotten except for his contribution to Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Hopwood achieved a material success that the older Miller could not match, but he failed to capture the immortality that would be Miller’s. Hopwood’s suicide, on the beach of the Cote d’Azur, reportedly inspired Norman Maine’s march into the southern California surf in A Star Is Born (1937).

Like Fitzgerald, Miller tasted success at a tender age. In 1938, upon graduating from Michigan, he received a Theatre Guild National Award and returned to New York, joining the Federal Theatre Project. He married his college girlfriend, Mary Grace Slattery, in 1940; they would have two children, Joan and Robert. In 1944, he made his Broadway debut with “The Man Who Had All the Luck”, a flop that lasted only four performances. He went on to publish two books, “Situation Normal” (1944) and “Focus” (1945), but it was in 1947 that his star became ascendant. His play “All My Sons”, directed by Elia Kazan, became a hit on Broadway, running for 328 performances. Both Miller and Kazan received Tony Awards, and Miller won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. It was a taste of what was to come.

Staged by Kazan, “Death of a Salesman” opened at the Morosco Theatre on February 10, 1949, and closed 742 performances later on Nov 18, 1950. The play was the sensation of the season, winning six Tony Awards, including Best Play and Best Author for Miller. Miller also was awarded the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. The play made lead actor Lee J. Cobb, as Willy Loman, an icon of the stage comparable to the Hamlet of John Barrymore: a synthesis of actor and role that created a legend that survives through the bends of time. A contemporary classic was recognized, though some critics complained that the play wasn’t truly a tragedy, as Willy Loman was such a pathetic soul. Given his status, Loman’s fall could not qualify as tragedy, as there was so little height from which to fall. Miller, a dedicated progressive and a man of integrity, never accepted that criticism. As Willy’s wife Linda said at his funeral, “Attention must be paid”, even to the little people.

In 1983, Miller himself directed a staging of “Salesman” in Chinese at the Beijing People’s Art Theatre. He said that while the Chinese, then largely ignorant of capitalism, might not have understood Loman’s career choice, they did have empathy for his desire to drink from the Grail of the American Dream. They understood this dream, which Miller characterizes as the desire “to excel, to win out over anonymity and meaninglessness, to love and be loved, and above all, perhaps, to count.” It is this desire to sup at the table of the great American Capitalists, even if one is just scrounging for crumbs, in a country of which President Calvin Coolidge said, “The business of America is business,” this desire to be recognized, to be somebody, that so moves “Salesman” audiences, whether in New York, London or Beijing.

Miller never again attained the critical heights nor smash Broadway success of “Salesman,” though he continued to write fine plays that were appreciated by critics and audiences alike for another two decades. Disenchanted with Kazan over his friendly testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, the two parted company when Kazan refused to direct “The Crucible”, Miller’s parable of the witch hunts of Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Defending her husband, Kazan’s wife, Molly, told Miller that the play was disingenuous, as there were no real witches in Puritan Salem. It was a point Miller disagreed with, as it was a matter of perspective–the witches in Salem were real to those who believed in them. However, subsequent research has shown that the cursorily-researched (at best) play contains fictional motifs (regarding Goodman and Goodwife Putnam and their offspring), limited research, and carelessness in identifying (or not identifying, as with William Stoughton) the true authors of the witch trials. Directed by another Broadway legend, Jed Harris, the play ran for 197 performances and won Miller the 1953 Tony Award for Best Play. Miller had another success with “A View from the Bridge”, a play about an incest-minded longshoreman written with overtones of classical Greek tragedy, which ran for 149 performances in the 1955-56 season.

It was in 1956 that Miller made his most fateful personal decision, when he divorced his first wife, Mary Slattery Miller, and married movie siren-cum-legend Marilyn Monroe. With this marriage Miller achieved a different type of fame, a pop culture status he abhorred. It was a marriage doomed to fail, as Monroe was, in Miller’s words, “highly self-destructive”. In his 1989 autobiography, “Timebends”, Miller wrote that a marriage was a conspiracy to keep out the light. When one or more of the partners could no longer prevent the light from coming in and illuminating the other’s faults, the marriage was doomed. In his own autobiography, “A Life”, Kazan said that he could not understand the marriage. Monroe, who had slept with Kazan on a casual basis, as she did with many other Hollywood players, was the type of woman someone took as a mistress, not as a wife. Miller, however, was a man of principle. He was in love. “[A]ll my energy and attention were devoted to trying to help her solve her problems”, Miller confessed to a French newspaper in 1992. “Unfortunately, I didn’t have much success.”

The conspiracy collapsed during the filming of The Misfits (1961) (1961), with John Huston shooting the original script Miller had written expressly for his wife. The genesis of the story had come to him while waiting out a divorce from his first wife Mary in Nevada. Monroe hated her character Roslyn, claiming Miller had made her out to be the dumb blond stereotype she so loathed and had been trying to escape. Withering in her criticism of Miller, and ultimately unfaithful to him, she and Miller separated. Norman Mailer, in his 1973 biography, “Marilyn”, ridiculed Miller for not doing enough to help Monroe. Film critic Pauline Kael lambasted Mailer by imputing petty machismo and jealousy as the cause of his animus against Miller. Miller would later reunite with Kazan to launch the new Lincoln Center Repertory Theater, with the play “After the Fall”, a fictionalization of his relationship with Monroe. “Fall” ran for 208 performances in repertory in 1964 and 1965 and won 1964 Tony Awards for Jason Robards and Kazan’s future wife Barbara Loden, playing the Miller and Monroe stand-ins Quentin and Maggie. Miller’s own “Incident at Vichy” played in repertory with “Fall” in the 1965 season, but lasted only 32 performances.

On June 1, 1957, Miller was found in contempt of Congress for refusing to name names of a literacy circle suspected of Communist Party affiliations. The State Department deprived him of his passport, and he became a left-wing cause célèbre. In 1967 Miller became President of P.E.N., an international literacy organization that campaigned for the rights of suppressed writers. He published a collection of short stories entitled “I Don’t Need You Any More”, that same year. Returning to the Morosco Theatre, the site of his greatest triumph, “The Price” was Miller’s last unqualified hit in America, running for 429 performances between February 7, 1968 and February 15, 1969. Though Miller won a 1968 Tony Award for Best Play, the bulk of his success as an original playwright was over. The Price (1971) (a 1971 teleplay) was nominated for six Emmy awards, including Outstanding Single Program-Drama or Comedy, and won three, including Best Actor for George C. Scott, who would later win a 1976 Tony playing Willy Loman in a 1975 Broadway revival.

Miller never again achieved success on Broadway with an original play. In the 1980s, when he was hailed as the greatest living American playwright after the death of Tennessee Williams, he even had trouble getting full-scale revivals of his work staged. One of his more significant later works, “The American Clock”, based on Studs Terkel’s oral history of the Great Depression, “Hard Times”, ran for only 11 previews and 12 performances in late 1980 at the Biltmore Theatre. Also in 1980, Miller courted controversy by backing the casting of the outspokenly anti-Zionist Vanessa Redgrave as a concentration-camp Jewess in his teleplay Playing for Time (1980), an adaptation of the memoir “The Musicians of Auschwitz”. Despite the fallout in the United States for America’s then-greatest living playwright, his works were popular in Great Britain, whose intellectual and theatrical communities treated him as a major figure in world literature. The universality of his work was highlighted with his own successful staging of “Death of a Salesman” in Beijing in 1983.

“Death of a Salesman” has become a standard warhorse, now revived each decade on Broadway, and internationally. In addition to George C. Scott and Lee J. Cobb (who received an Emmy nomination for the 1966 teleplay; Miller himself received a Special Citation from the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for the production), Dustin Hoffman and Brian Dennehy have garnered kudos for playing Willie Loman. The 1984 Broadway revival of “Salesman” won a Tony for best Reproduction and helped revive Miller’s domestic reputation, while Volker Schlöndorff’s 1985 film (Death of a Salesman (1985)) of the production won 10 Emmy nominations, including one for Miller as executive producer of the Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special. Hoffman won an Emmy and a Golden Globe for playing Willy Loman. The 1999 revival won four Tonys, including Dennehy for Best Actor, and ran for 274 performances at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre. Arthur Miller died in Roxbury, Connecticut in 2005, aged 89. He had been suffering from cancer, pneumonia and a heart condition.

Miller based his works on American history, his own life, and his observations of the American scene. His stature is traditionally based on his perceived refusal to avoid moral and social issues in his writing. His willingness to fight for what he believed in his chosen art form made him a literary icon whose name will live on in world letters.