First of all, the cross-eyed comedian of silent days was not born that way. Supposedly his right eye slipped out of alignment while playing the role of the similarly afflicted Happy Hooligan in vaudeville and it never adjusted. Ironically, it was this disability that would enhance his comic value and make him a top name.

Ben Turpin was born in New Orleans in 1869, the son of a French-born confectionery store owner. When 7 years old, his father moved to New York’s lower East Side. A wanderlust fellow by nature, Turpin lived the life of a hobo in his early adult years. He started up his career by chance while bumming in Chicago where he drew laughs at parties. An ad in a newspaper looking for comedy acts caught his eye and he successfully booked shows along with a partner. Going solo, he performed on the burlesque circuit as well as under circus tents and invariably entertained his audiences by doing tricks, vigorous pratfalls and, of course, crossing his eyes. One of his more familiar sight gags was a backwards tumble he called the “108.” He happened upon the Happy Hooligan persona while playing on the road and kept the hapless character as part of routine for 17 years.

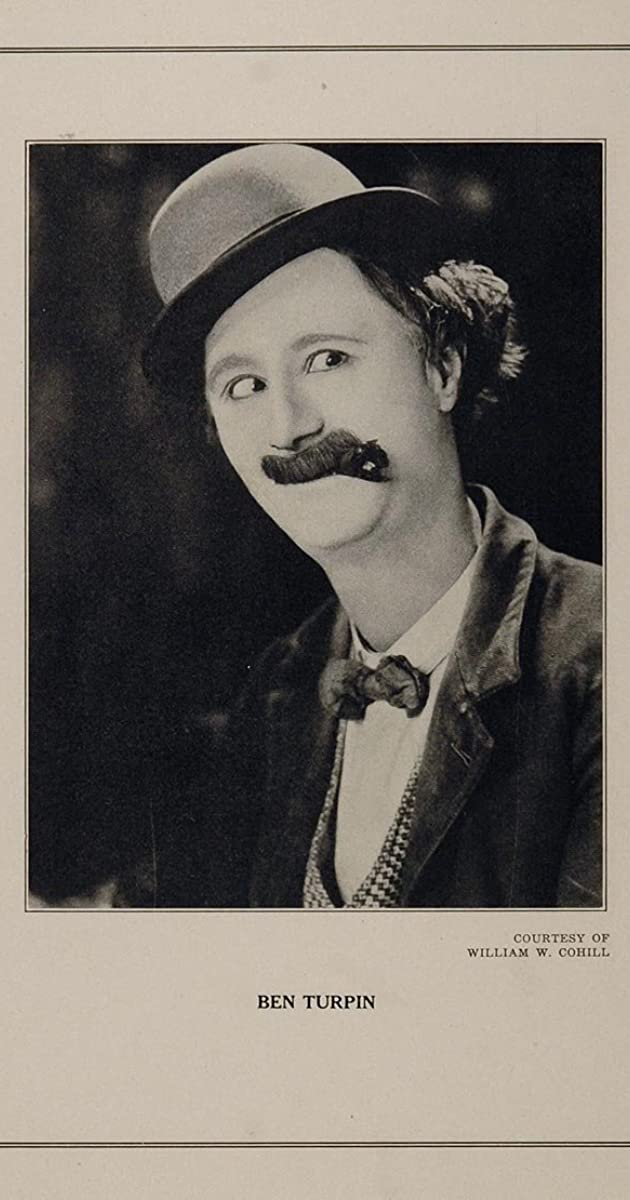

He started in films at age 38 in 1907, joining Essanay Studios shortly after the company began operating in Chicago. He also became their resident janitor for a spell. He stayed with the company for two years but remained on the edges of obscurity. Appearing sporadically in silent comedy shorts, he typically played dorky characters who always did something wrong. His big break came when he returned to Essanay and was introduced to Charles Chaplin, who immediately took to him and set him up with Mack Sennett. By 1917 Sennett had turned Turpin into a top comedy draw. With his trademark crossed eyes and thick mustache, he made scores of slapstick films alongside the likes of Mabel Normand and ‘Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle’, among others. Most notable were his films that parodied hit movies of the day such as his The Shriek of Araby (1923), in which his character lampooned Rudolph Valentino. Turpin’s true forte was impersonating the most dashingly romantic and sophisticated stars of the day and turning them into clumsy oafs.

Turpin retired from full time acting in 1924 to care for his ailing wife Canadian comedy actress Carrie Turpin (nee LeMieux). After her death the following year he returned but his marquee value had slipped drastically. The advent of sound pretty much marked the end to his special brand of physical comedy. He was only glimpsed from then on, mostly in comic cameos for other top stars such as a bit as a plumber with Laurel & Hardy in Saps at Sea (1940), his last. He died of heart disease that same year.