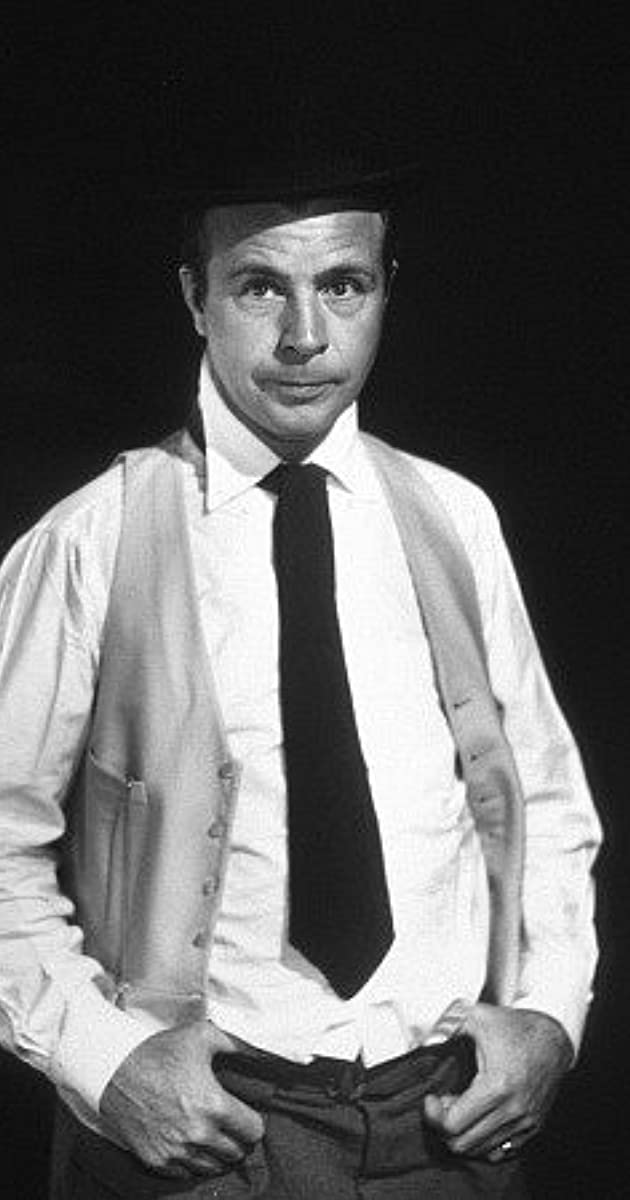

Few actors ever managed a complete image transition as thoroughly as did Dick Powell: in his case, from the boyish, wavy-haired crooner in musicals to rugged crime fighters in films noir. Powell grew up in the town of Little Rock, Arkansas, one of three brothers (one of them, Howard, ended up as vice president of the Illinois Central Railroad). He worked his way through schooling, sidelining as a soda jerk and a grocery clerk before entering the world of show biz as a singer (tenor) and banjo player with the Royal Peacock Orchestra in Louisville, Kentucky. He then got a gig with the Charlie Davis band and toured with them throughout the mid-west, appearing at dance halls and picture theatres. He next worked as a master of ceremonies and this rounded him off as an entertainer even before he was signed by a Warner Brothers talent scout in 1932. Looking rather younger than his actual years, Powell soon found himself typecast as clean-cut singing juveniles in a series of exuberant musicals with lavish production numbers like 42nd Street (1933), one of two dozen similar pictures he made for the studio.

In 1935, Powell’s salary amounted to $70,000. Two years later, he had become one of Hollywood’s top ten box office stars, yet was paid just half of what he had earned as an MC. A keen businessman with an eye for profit, Powell had already invested wisely in land and property. When he left Warners in 1939 with no discernible acting opportunities in sight, he was in no way short of a quid. He was, however, desperate to escape his image, declaring “I knew I wasn’t the greatest singer in the world and I saw no reason why an actor should restrict himself to any one particular phase of the business”. He fairly jumped at the chance to act in non-singing roles, joining Paramount in 1940 to appear opposite Ellen Drew in the sparkling Preston Sturges comedy Christmas in July (1940). This was followed by two marital farces featuring his then-wife, Joan Blondell, both efforts receiving only a lukewarm response at the box-office. Still dissatisfied with lightweight roles, Powell lobbied hard to get the lead (eventually scored by Fred MacMurray) in Double Indemnity (1944) but was knocked back. Instead, he was slotted into more of the same fare, refused to comply and was suspended.

His box office credo now at a low ebb, Powell tried his luck at RKO and at last managed to secure a lucrative role: that of hard-boiled private eye Philip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s Murder, My Sweet (1944). The author himself approved of the casting, though the director (Edward Dmytryk) fought off initial misgivings. The result proved nothing if not a tangible hit for RKO. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times remarked ” …and while he may lack the steely coldness and cynicism of a Humphrey Bogart, Mr. Powell need not offer any apologies. He has definitely stepped out of the song-and-dance, pretty-boy league with this performance”. In short order, offers suddenly kept coming. Having successfully reinvented himself, Powell now found steady work on radio, respectively as “Richard Rogue” and then “Richard Diamond, Private Eye”. In films, he remained on cue for wise-cracking tough guy roles in Cornered (1945) and Johnny O’Clock (1947). His most challenging role yet was as best-selling novelist James Lee Bartlow in MGM’s epic drama The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)]. Powell also dabbled at directing, though he only helmed six pictures in total: among them a minor film noir, Split Second (1953)], and an above-average submarine drama, The Enemy Below (1957)]. Having quit film acting in the mid-50s, he began to concentrate primarily on producing TV drama as host and executive producer of his own award-winning anthology show, The Dick Powell Show (1961). He was also co-founder and managing director of Four Star Television (which had its studios where Republic had formerly existed and which would subsequently become CBS Cinema Center).

Dick Powell died prematurely of lung cancer in January 1963 at the age of 58. He was survived by his third wife, the actress June Allyson.