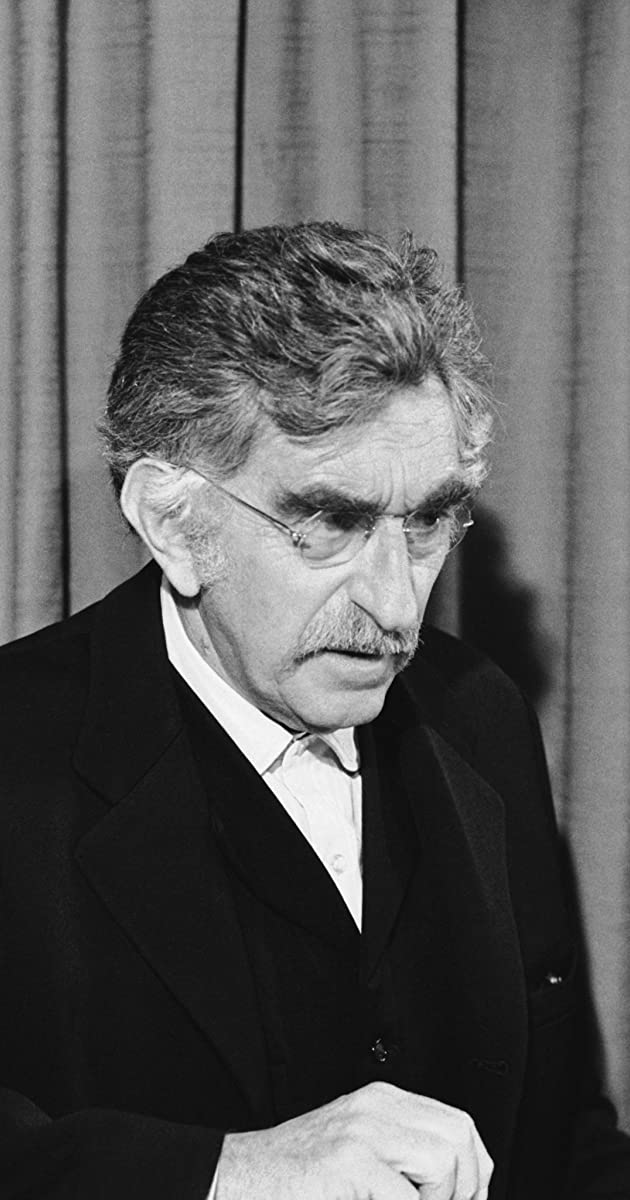

Jeff Corey was a film and television character actor, as well as one of the top acting teachers in America.

Corey was born Arthur Zwerling on August 10, 1914 in New York City, New York, to Mary (Peskin), a Russian Jewish immigrant, and Nathan Zwerling, an Austrian Jewish immigrant. He was an indifferent student, but after taking a drama class in high school, young Corey became hooked. His talent earned him a scholarship to the Feagin School of Dramatic Arts, the top acting school in New York City at the time. Corey then became a professional actor, a career choice which saved him from a life selling sewing machines, he later said.

His first gig after acting school was with a Shakespearean repertory company, after which he became a member of a traveling troupe that entertained children. After Leslie Howard closed his Broadway production of Hamlet in December 1936, he took the play on the road with Corey cast as Rosencrantz in 1937. In 1939, Corey appeared as part of the Federal Theater Project’s (FTP) Living Newspaper dramatic showcase in the Life and Death of an American, co-starring with Arthur Kennedy, and featuring the music of Alex North. He made his film debut in a bit part in the Federal Theater’s sole movie production, …One Third of a Nation… (1939). Starring Sylvia Sidney, Leif Erickson and future Oscar-winning director Sidney Lumet, the movie, which was released by Parmount, was a progressive exegesis on the hazards of tenement slum conditions. Congress terminated FTP funding on June 30, 1939, mainly due to objections to the leftist political tones of many FTP productions (see Tim Robbins’ movie Cradle Will Rock (1999) about the pressures faced by the FTP in 1939).

In 1940, Corey, who had married his wife Hope in 1938, moved to Hollywood, where he appeared in studio productions through 1943, including All That Money Can Buy (1941), My Friend Flicka (1943) and Joan of Arc (1948). He also had a hand in establishing the Actors Lab, where he appeared in a wide variety of plays, including “Abe Lincoln in Illinois”, “Miss Julie” and “Prometheus”. He also produced “Juno and the Paycock” for the Lab. He joined the United States Navy Photographic Service in 1943 and was assigned to the aircraft carrier Yorktown as a motion picture combat photographer. He earned three citations while serving during the war, including one for shooting footage on the Yorktown during a kamikaze attack on the ship. The citation, which was awarded in October 1945, read: “His sequence of a Kamikaze attempt on the Carrier Yorktown, done in the face of grave danger, is one of the great picture sequences of the war in the Pacific, and reflects the highest credit upon Corey and the U.S. Navy Photographic Service.”

After the war, Corey returned to Hollywood and resumed his acting career, specializing in character parts and playing heavies in films such as The Killers (1946) and Brute Force (1947), both of which starred another returning war vet, Burt Lancaster. His appearance as the psychiatrist in Home of the Brave (1949), one of his best screen performances, promised a long and productive career in Hollywood, but the first phase of his cinema career was cut short in 1951 when he was subpoenaed to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) after being named as a former Communist Party member by actor Marc Lawrence.

HUAC had scheduled hearings in Los Angeles as part of its crusade to ferret out Communist influence in Hollywood. Appearing before HUAC in Los Angeles in September 1951, the 37-year-old Corey refused to testify, instead invoking his 5th Amendment rights. The movie industry ruled that anyone invoking their constitutional right not to testify would be blacklisted, and Corey was, missing out on an entire decade of work in films and television during the 1950s. Ironically, Lawrence, whom Corey despised for the rest of his life, pointing out that he had remained stateside on a health deferment while Corey risked his life during the war, was virtually absent from American films and television during the same decade, having to make his living in Italy along with American expatriates who had been blacklisted.

In the book on Hollywood blacklistees “Tender Comrades”, Corey explained that he had been a member of the Communist Party, and that while he no longer was in 1951, he could not in good conscience turn informer. “Most of us were retired reds,” Corey said. “We had left it, at least I had, years before. The only issue was, did you want to just give them their token names so you could continue your career, or not? I had no impulse to defend a political point of view that no longer interested me particularly. They just wanted two new names so they could hand out more subpoenas.”

After being blacklisted, Corey used his G.I. Bill benefits to study speech therapy at UCLA while supporting his family as a common laborer. At the request of a fellow student, Corey organized a class in speech that he taught in the garage of his home in Hollywood Hills home. He expanded his curriculum to acting, accepting $10 a month in “tuition” per month from each student that allowed them to attend weekly classes. Eventually, he expanded the garage to create a small theater where his students performed scenes. Corey’s reputation as a teacher grew, and by the mid-1950s, he had become the premier acting coach in Hollywood. Although studios refused to hire the blacklisted Corey as an actor, they did send contract players to study with him.

Corey’s class, which became known as the Professional Actors Workshop, attracted directors, screenwriters and established actors seeking insight into the craft. Corey’s Workshop has been described by the National Observer as “A major influence in the motion picture industry.” Corey was a Stanislavskian teaching the popular Method technique of sense-memory popularized by such other acting gurus as Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler, which sought to tap into the actor’s own emotions and psyche. Corey’s own teaching technique was eclectic: He focused on one-on-one work with an individual actor, seeking through improvisational exercises to get the actor to tap into his/her subconscious and to use their imagination to come up with a theme that would elucidate their character.

His students included Robert Blake, pop singer Pat Boone, Richard Chamberlain, singer/actress Cher, director-producer Roger Corman, James Dean, Kirk Douglas, Jane Fonda, Peter Fonda, Michael Forest, Sally Kellerman, Irvin Kershner, Shirley Knight, Penny Marshall, Rita Moreno, Jack Nicholson, Leonard Nimoy, Anthony Perkins, Rob Reiner, singer/actress/director Barbra Streisand, future Academy Award-winning screenwriter Robert Towne and Robin Williams. Of Corey the teacher, three-time Oscar-winner Jack Nicholson said after he had become a major movie star, “Acting is life study, and Corey’s classes got me into looking at life as an artist.”

Corey also tutored experienced actors who had trouble with a role, or who just needed insight into playing a character. One of the already-established actors Corey tutored was three-time Oscar nominee Kirk Douglas, who came to Corey for help in playing the title role in Spartacus (1960). It was Douglas who, along with Otto Preminger, ended the blacklist by hiring Dalton Trumbo to write the screenplays for Spartacus (1960) and Exodus (1960), respectively. Two years after the Trumbo-penned films debuted on the big screen, Corey again was working in films and television. In 1962, he was cast in the film The Yellow Canary (1963) when one of his acting students, pop singer Pat Boone, pressured 20th-Century Fox into hiring him. Now off the blacklist, Corey became a busy character actor in movies and on television. Corey made his reputation as an actor’s actor whom other actors loved to work with. Always good with actors, Corey also directed some episodes of television series.

In addition to his acting work, Corey continued teaching. He was Professor of Theater Arts at California State University in Northridge, and was artist in residence at Ball State, in Indiana, the University of Illinois in Bloomington, Chapman College’s World Campus Afloat, the University of Texas in Austin, and at the Graduate School of Creative Writing at New York University. He also conducted acting seminars at Emory University in Atlanta, and for the Canadian Film Institute in Vancouver, British Columbia.

On August 16, 2002, six days after his 88th birthday, Corey died in a Santa Monica, California hospital, of complication from a fall. He was survived by his wife of 64 years, Hope, three daughters, and grandchildren.