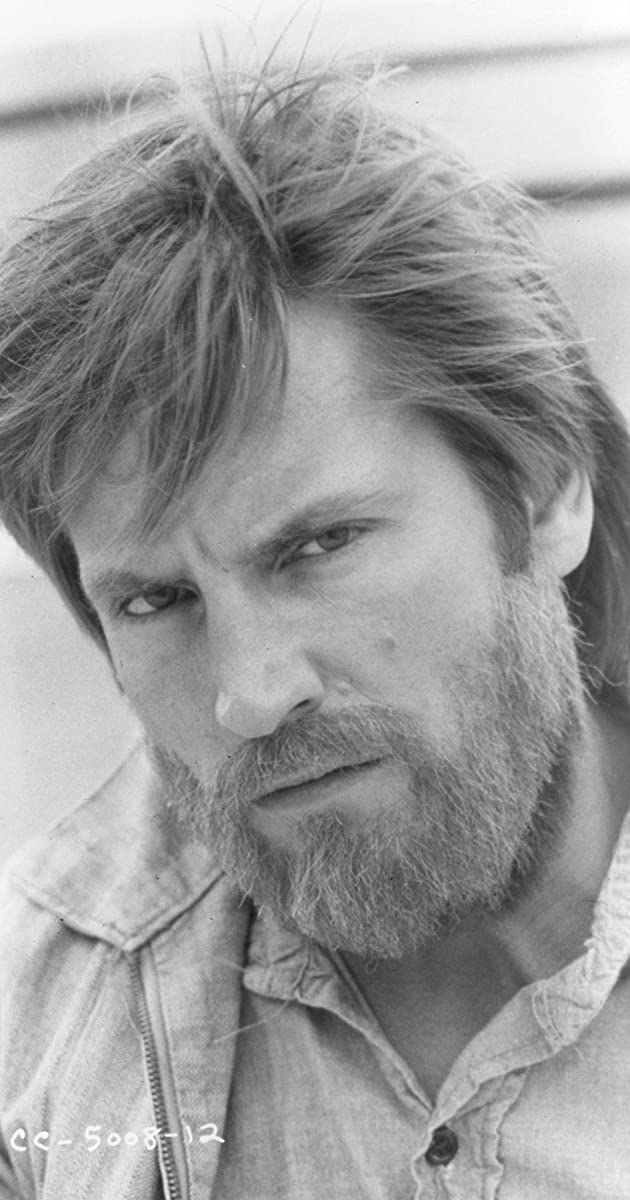

Joe Dallesandro’s still hangin’ . . . after battles with drug addiction and alcohol, brushes with the law, three broken marriages and numerous love affairs, plus the suicide of his only sibling Bob. One of the most beautifully photographed wild guys to come out of the Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey “Factory” era, the slight and slightly androgynous Dallesandro became an improbable pioneer of the male sexual revolution and the first film actor to be glorified as a nude sex symbol. The Morrissey/Warhol movies were known for their bizarre, amateur standing, yet Joe and his completely uninhibited, walk-on-the-wild-side demeanor managed to hold an entire underground audience captive. Joe’s dangerous street mentality and raw erotic power became a definitive turn-on to both gay and straight audiences and his fame eventually filtered somewhat into the mainstream.

Born humbly as Joseph Angelo D’Alessandro III in Pensacola (located on Florida’s panhandle) on New Year’s Eve in 1948, his parents, Joe II and Thelma, were teenagers when Joe was born; his father was a Navy man stationed there and his mother had a wild streak of her own. Joe (then age 5) and younger brother Robert were placed into a New York adoption facility after Thelma was given a five-year prison sentence for auto theft and the father decided he was unable to care for them alone. Brought up in a series of foster homes, Joe became notorious for his delinquent behavior at school — which was often ignited by his short stature and even shorter temper. Frequent runaways, he and his brother eventually returned to live with their grandparents but Joe quickly drifted towards a life of crime (thievery, burglary, etc.) via his association with street gangs.

At 15 “Little Joe” was caught stealing a car and sentenced to a juvenile rehab facility in New York’s Catskill Mountains. During this time he started his famous “Little Joe” tattoo body markings. He escaped from the facility and lived a nomadic life in Mexico for a time before returning to the US (Los Angeles), where he gained unexpected acceptance in the California gay scene. The wanderlust teen found it profitable to exploit his sulky good looks and smoothly-muscled physique by posing nude for various photographers in the mid-’60s. Sometimes billed as “Joe Catano”, Dallesandro hit many of the underground studios in both California and New York, working most notably for Robert Henry Mizer, who founded the Athletic Model Guild (AMG), and Bruce Bellas, aka Bruce of Los Angeles. A little magazine called Physique Pictorial, which was passed off as a bodybuilding publication, was, in truth, geared heavily toward its gay subscribers. Many were clients of Mizer, who photographed thousands of buff young men (some even out-of-work military servicemen) in various stages of undress from 1945-1993. Joe became Mizer’s most famous model and can be seen featured in Thom Fitzgerald’s docudrama Beefcake (1998), which chronicles the Mizer AMG era.

Back in New York during the summer of 1967, the 18-year-old, while visiting a friend in Greenwich Village, was invited to sit in and watch Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey shooting an impromptu marathon movie in Warhol’s building apartment. Morrissey’s camera quickly found its way toward the ambivalent, good-looking Joe and the rest is history. Joe wound up shooting a wrestling scene with another guy clad only in his underwear. A year later that 23-minute footage found its way into The Loves of Ondine (1968), an 86-minute mishmosh of Warhol’s eccentric ideas. Joe’s image in his jockey shorts was used for the primary ads in The Village Voice. The movie, which featured his extended improvised wrestling scene, was reviewed by Variety and Joe himself, surprisingly, received raves for his charismatic good looks and natural acting ability, and was touted as a possible legit performer.

Young Dallesandro instead became Morrissey’s protégé. Although Joe displayed beefcake appeal in Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys (1968), which was investigated by the FBI for rumors of an on-screen rape, and San Diego Surf (1968), the only Warhol feature film never released, it was Morrissey’s film trilogy that led to Joe’s subsequent idol worship. The first, Flesh (1968), placed Joe front-and-center as a male hustler á la Midnight Cowboy (1969). Intended for female and gay audiences, Joe hit counterculture fame as the first actor to offer extensive full-frontal nudity and the movie also managed to filter successfully out to mainstream audiences.

Morrissey’s second feature, Trash (1970), was anointed a “masterpiece” and “best film of the year” by none other than Rolling Stone magazine. In it Little Joe plays a heroin junkie living in New York squalor with girlfriend Holly Woodlawn (Warhol’s well-known transvestite actress). The last of Morrissey’s trilogy, Heat (1972) takes place in the vicinity of L.A.’s Sunset Boulevard with a long, pony-tailed Joe as a cold-hearted ex-child star who beds down everyone, including seamy “Midnight Cowboy” actress Sylvia Miles and her lesbian daughter, in order to resuscitate his long-dormant career. This attention led to Joe’s making the cover of Rolling Stone in April 1971. He was also photographed by some of the top celebrity photographers of the time, including Francesco Scavullo, and Richard Avedon. Singer/songwriter Lou Reed utilized Little Joe’s identity in his pop hit “Walk on the Wild Side”. In Europe Morrisey’s films were praised even more, while Dallesandro was placed on an erotic pedestal.

Acting pay was practically non-existent so Dallesandro, now a husband (to wife Leslie, who was the daughter of one of his dad’s girlfriends) and father (their son Michael), received “Factory” pay by answering phones, checking in and checking out film prints, acting as a projectionist, handling security and even running the building’s elevator. Morrissey’s hot trilogy was followed by the European cult films Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974), both eclectic X-rated blood spillers and ultimate cult items.

Tired of being just a gear in the Factory machinery, Joe stayed on in Europe after filming the two 1974 gorefests and decided to see if his Warhol Superstar status could trigger foreign box-office career a la the recently transported Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson. Joe made 18 feature films overseas throughout the rest of the 1970s. They were a mixture of styles: the sex-farce Donna è bello (1974); the gritty, grimy crime yarn L’ambizioso (1975) [“The Climber”]; _Louis Malle’s adult version of Alice in Wonderland, Black Moon (1975); The Streetwalker (1976) [“The Streetwalker”] co-starring softcore erotica star Sylvia Kristel; the sexually taunting Vacanze per un massacro (1980) as a car thief-turned hostage taker; Jacques Rivette’s surrealistic Merry-Go-Round (1981); Tapage nocturne (1979) [“Nocturnal Uproar”] as a self-absorbed actor; and Queen Lear (1982), a Franco-Swiss co-production in which he plays a bisexual.

The best of Joe’s European films, and his personal favorite, is the sexually-charged Je t’aime moi non plus (1976) [“I Love You, I Don’t”], Serge Gainsbourg’s film wherein he plays a gay garbage truck driver who has the hots for a very boyish café waitress Jane Birkin (Gainsbourg’s wife at the time).

Returning to the States in 1980, Joe’s work became more erratic than erotic, but some of his roles have earned a bit of attention. More noteworthy was his gangster Lucky Luciano in Francis Ford Coppola”s The Cotton Club (1984); another gangster in the Bruce Willis starrer Sunset (1988); his religious zealot in John Waters’ mainstream Cry-Baby (1990); his psychotic paratrooper in Private War (1988); his trailer park scum who lusts after ‘Drew Barrymore’ in Guncrazy (1992); his sleazy photographer in _L.A. Without A Map (1998)_, and his brain-damaged hit man in Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey (1999). On TV he made standard guest appearances on such popular shows as Miami Vice (1984), Wiseguy (1987) and Matlock (1986).

The Teddy Award, an honor recognizing those filmmakers and artists who have contributed to the further acceptance of LGBT lifestyles, culture, and artistic vision, was awarded to Joe in February of 2009. A biography, “Little Joe: Superstar” by Michael Ferguson was released earlier in 2001 and a filmed documentary, Little Joe (2009), has been released with Joe serving as writer and producer. The thrice-married and divorced actor has two sons, Michael and Joe, Jr. Glimpsed here and there these days, he later managed a hotel in the Hollywood area.