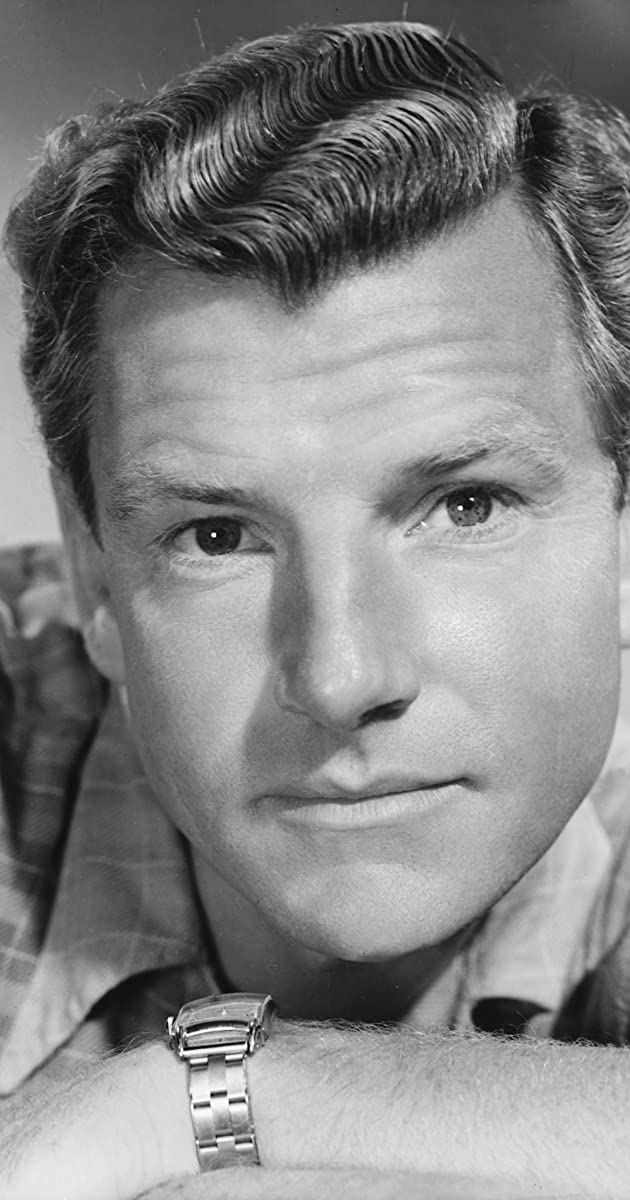

Affable, bright and breezy Kenneth More epitomised the traditional English virtues of fortitude and fun. At the height of his fame in the 1950s he was Britain’s most popular film star and had appeared in a string of box office hits including Genevieve (1953), Doctor in the House (1954), Reach for the Sky (1956) and A Night to Remember (1958).

Later in his career, when the film industry declined, he turned his talents to television where his interpretations of Jolyon in BBC’s The Forsyte Saga (1967) and the title role in Father Brown (1974) made him a household name all over again.

More was a shrewd man when it came to the business of acting. He knew his limitations and what roles suited him. When the director Sir Peter Hall once suggested he play Claudius to Albert Finney’s Hamlet at the Royal National Theatre, More declined saying; “one part of me would like to, but the other part said that there were so many great Shakespearian actors who could have done it better. I stick to the roles I can play better than them.”

Born in Gerrards Cross in 1914, More’s early grounding was in variety and legitimate theatre in the UK. On screen, like many leading men in the 1950s such as John Mills and Jack Hawkins, he seemed to spend most of the decade in uniform. When he read Reach for the Sky (1956), the biography of the legless wartime pilot Douglas Bader, he was desperate to play the role, even though it was earmarked for Richard Burton. “I knew I was the only actor who could play the part properly” he said. “Most parts that can be played by one actor can equally well be played by another, but not this. Bader’s philosophy was my philosophy. His whole attitude to life was mine.”

Films such as North West Frontier (1959) and Sink the Bismarck! (1960) kept More at the top although his favourite role was as the down-at-heel actor in The Greengage Summer (1961).

His private life was colourful and he was rarely out of the newspaper headlines. He was married three times, lastly to the actress Angela Douglas, whom he met whilst filming Some People (1962) with her.

His drinking companions were the hellraisers Trevor Howard and Jack Hawkins. Noël Coward once tried to seduce him in a bedroom but More gasped; “Oh, Mr Coward, sir – I could never have an affair with you, because you remind me of my father!”

Asked to sum up his enduring appeal, More said: “A film like Genevieve (1953) to my contemporaries is not a film made years ago, but last week or last year. They see me as I was then, not as I am now. I am the reassurance that they have not changed. In an upside down world, with all the rules being rewritten as the game goes on and spectators invading the pitch, it is good to feel that some things and some people seem to stay just as they were.”