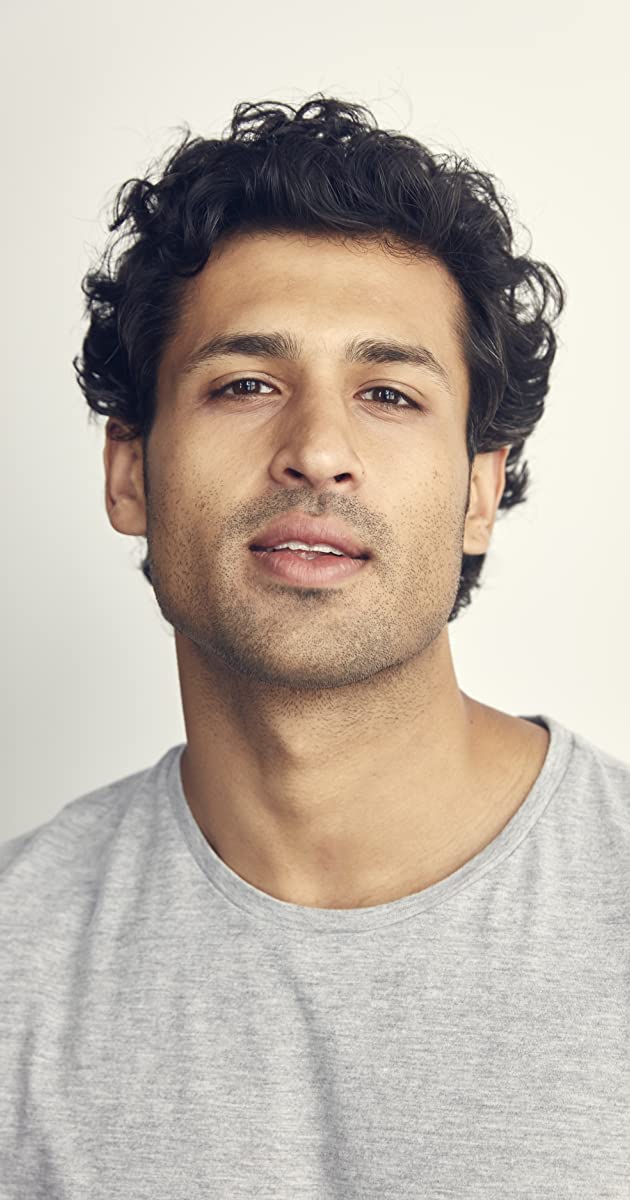

Seemingly suave, cultivated actor by nature, definitely huge in both talent and girth, and capable of playing much older than he was, Hollywood of the early ’40s tragically lost Laird Cregar before it could fully comprehend on how to best utilize his obvious gifts. He was born Samuel Laird Cregar in a well-to-do section of Philadelphia, eventually dropping his first name after forging an acting career. At age eight his parents sent him to England and enrolled him at the Winchester Academy. During his school’s off time, his pique in acting escalated after being employed as a page boy with the Stratford-on-Avon Players. Thereafter, his mind was set to become a professional actor. Returning to the U.S., he attended Episcopal Academy in Philadelphia and the Douglas Adams School in Longport, New Jersey. Again, he found meager jobs, such as an usher, in order to stay close to the theater. Awarded a scholarship to the Pasadena Community Playhouse, he trained there for two years before going out on his own and finding minor work on the bi-coastal stage and finding minuscule parts in films.

Laird’s break came of his own making. After witnessing Robert Morley’s triumph in the title role of “Oscar Wilde” on Broadway, Laird set upon finding backing for his own version of the play. Debuting in Los Angeles and finding resounding success there as well as in San Francisco, film studios began competing for his services with Twentieth Century-Fox winning out. He made his feature debut opposite Paul Muni in Hudson’s Bay (1941) in the boisterous role of a fur trapper and solidified his movie standing by appearing flamboyantly as a bullfighting critic at odds with Tyrone Power’s matador in the popular Technicolor classic Blood and Sand (1941). He then went on to show a scene-stealing prowess for stylish farce as one of Jack Benny “suitors” in the drag comedy Charley’s American Aunt (1941).

By the time Laird cut a mean, sinister path in I Wake Up Screaming (1941), playing a detective so insanely hung up on a murdered girl (Carole Landis) that he deliberately frames an innocent man (Victor Mature) for her crime, it was obvious films could rely on him for any of their comedic or dramatic ventures. There seemed nothing he couldn’t do, but it was obvious audiences loved him as the 300 lb. man you love to hate – goaded on by his nefarious doings in the film noir classic This Gun for Hire (1942) starring Alan Ladd and Rings on Her Fingers (1942) with Gene Tierney.

On the Los Angeles theater front he gave Monty Woolley a run for the money in Woolley’s signature stage role of Sheridan Whiteside in “The Man Who Came to Dinner”. Along with the good came some contrived roles in a few mediocre films ranging from training officers to hammy-styled pirates. Even so, he usually stood out among the other actors in some fashion. He even played the Devil himself in the exquisitely humor-laced Ernst Lubitsch comedy Heaven Can Wait (1943).

His film career was capped by his definitive Jack the Ripper in The Lodger (1944). Investing the psychotic role with an intense, gripping realism and off-putting, oily charm, he led a brilliantly seasoned cast and relished a death scene in the film (in truth, the real-life serial killer was never caught) that dared to forever stereotype him as a Sydney Greenstreet-like villain. Unfortunately, his early death robbed film audiences of seeing what course Laird’s career would have taken. Sure enough, his last celluloid offering in Hangover Square (1945) was as another despicable character with murder on its maniacal mind. Top-lining a cast that included Linda Darnell (as an object of his affection), and George Sanders, he this time portrayed a temperamental composer who suffers from a split personality disorder and, prone to periodic blackouts, commits brutal murders. Another compelling death scene had his mad character wildly pounding out a concerto while the room around him goes up in flames and the ceiling crashes down on him.

Laird’s obsession with avoiding the inevitable stereotype as a “heavy heavy” and wistful pursuit of a romantic leading man career compelled him to go on a reckless, unsupervised crash diet (from 300 lbs to 200 lbs), which is evident by his drastically trimmed-down look in his last film. This proved too strenuous on his system and he was forced to undergo surgery for a severe stomach disorder. His 30-year-old heart gave out on the morning of December 9, 1944, only days after his operation. He was survived by his mother.