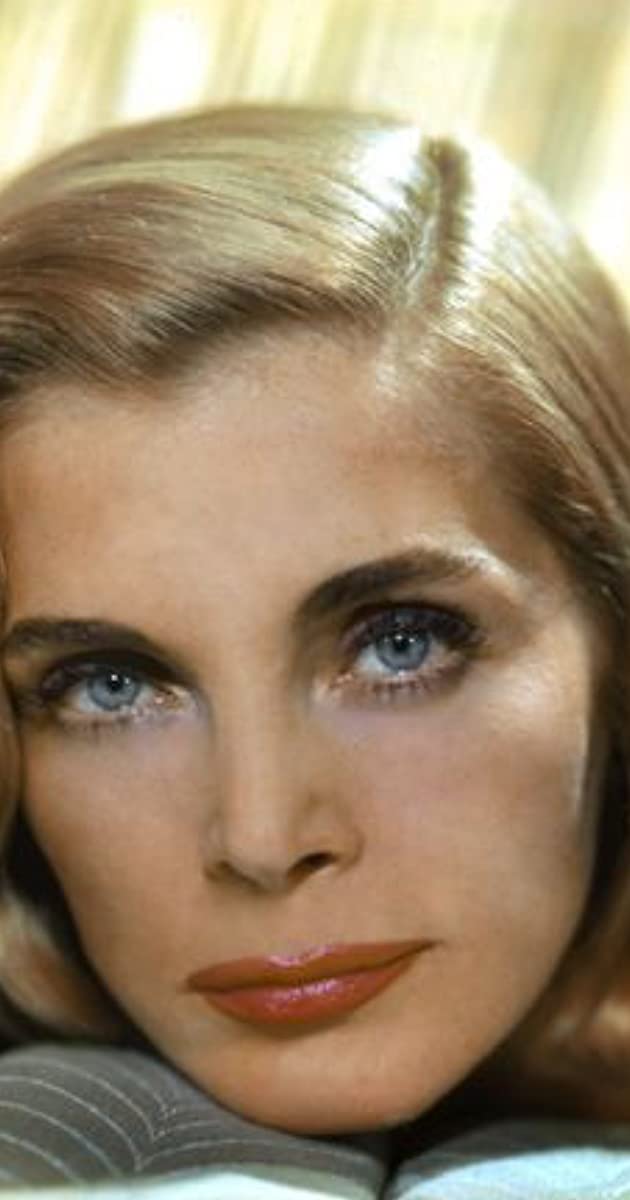

Lizabeth Scott was born Emma Matzo on September 29, 1922 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the oldest of six children of Mary (Pennock) and John Matzo, who were Slovak immigrants. Scott attended Marywood Seminary and the Alvienne School of the Theatre in New York City, where she adopted the stage name of “Elizabeth Scott.” After doing a national tour of Hellzapoppin, she was discovered by Broadway producer Michael Myerberg in 1942. Scott was the understudy for Tallulah Bankhead in the original Broadway production of “The Skin of Our Teeth.” Later in 1943, a Warner Brothers producer, Hal B. Wallis, discovered Scott at her 21st birthday party held at the Stork Club in New York. Wallis scheduled an interview with Scott the following day, but Scott canceled it when a telegram asked her to replace Miriam Hopkins at the Boston production of The Skin of Our Teeth.

In 1944, Scott was invited to Los Angeles by agent Charles K. Feldman, who saw her photos in “Harpers Bazaar.” After failed screen tests at Universal, International, then Warner Brothers, Scott again met Wallis, who said he would hire her if he had the power. Scott mistakenly believed that Wallis was as powerful as Jack L. Warner, and did not believe him. The day Scott left for New York, she read in Variety that Wallis resigned from Warner and formed his own production company, releasing films primarily through Paramount. A few months later, she returned from New York and was finally signed to Paramount. Scott appeared in 21 films between 1945 and 1957, though loaned out for half of her films to United Artists, RKO and Columbia. When Scott was introduced to the public in 1945, Paramount publicity releases, exaggerating her background, claimed Scott was a debutante, that her grocer father was an English-born, New York banker, and that her mother was a White Russian aristocrat.

Scott’s first film was You Came Along (1945), with Robert Cummings as the leading man. This Ayn Rand scripted film introduced the 23-year old smoky blonde to the American public. In a role originally intended for Barbara Stanwyck, Scott played a US Treasury PR flack that falls in love with an Army Air Force officer, who tries to hide his terminal leukemia. Despite Scott’s difficulties with director John Farrow, who lobbied for Teresa Wright, the film remains one Scott’s favorites.

On the strength of her first performance, Wallis starred Scott in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) over Stanwyck’s protests. Scott ended up in third place at the top behind Stanwyck and Van Heflin, with Kirk Douglas, in his film debut, billed below the three stars. The film is actually two in one, with Stanwyck and Scott inhabiting two parallel worlds, both linked by Heflin. The female leads have only one brief scene together. The director, Lewis Milestone, swore never to work with Wallis again, who wanted to re-shoot all of Scott’s scenes, which Wallis had to do personally. The film boasts an Oscar nominated screenplay by screenplay by Robert Rossen, music by Miklós Rózsa, art direction by Hans Dreier, and costumes by Edith Head.

In Scott’s third film, she is cast with Humphrey Bogart in Dead Reckoning (1947). It is Scott’s first crack as the archetypal femme fatale. In Dead Reckoning she lures Bogart into a web of lies, and deceit. As is typical in the noir genre, her power is rooted in her beauty and sexual allure. In a departure from his tough guy roles, Bogart plays a wronged man (a noir hero), who struggles to learn the fate of a missing army buddy. Scott is the ex-girlfriend who knows more than she lets on. To keep Bogart from learning the truth about his lost friend and his mysterious double life, Scott seduces him into believing she loves him.

In her fourth film, Scott appeared in the second noir to be shot in color, Desert Fury (1947), a coming-of-age story scripted again by Robert Rossen, based on the novel “Desert Town” by Ramona Stewart. Mary Astor is Fritzi Haller, a casino and bordello owner who runs the corrupt town of Chuckawalla, Nevada. She controls everyone in town, including the judge and sheriff’s office. The only one who dares defy Fritzi is her rebellious daughter Paula (Scott), who returns home after being expelled from another private school. When John Hodiak, a professional gambler, comes to town, Paula falls in love with him and trouble ensues. Then newcomers Burt Lancaster and Wendell Corey also appear.

In 1947, Scott was again cast with Lancaster and Kirk Douglas in I Walk Alone (1947), a story of betrayal and vengeance. Scott plays a nightclub singer who provides sympathy and support to Lancaster, recently released from prison to collect a debt, but is double-crossed by the Douglas character. Scott rises above it all and is completely convincing in her portrayal. Scott’s character provides a degree of romanticism and humanism usually lacking in film noir.

Film number seven was Pitfall (1948). Dick Powell played a middle-level insurance investigator, married to his high school sweetheart, Jane Wyatt. They living out a comfortable but boring existence in a post-war Los Angeles suburb. Powell is restless and unfulfilled (“I feel like a wheel within a wheel within a wheel”) when he receives what at first seems like a routine assignment to recover goods that have been bought with stolen money, a claim paid off by Powell’s firm. The items are traced to Mona Stevens (Scott), a model living in Marina Del Rey. Powell is attracted to her, and what starts out as innocent flirtation ends up in a passionate love affair. Powell’s journey into a daydream turns into a nightmare as he becomes a prisoner in his own home and kills an assailant, who has been set on his trail by a jealous private investigator, played by Raymond Burr. Meanwhile, the Burr character also blackmails Mona into doing private “fashion shows.”

In Too Late for Tears (1949), Scott played an avaricious Jane Palmer, a wife who goes to any length to keep $60,000 that is accidentally thrown in the back of her husband’s car. She eventually leaves behind a string of bodies in an effort to keep the money. This film is widely regarded by critics and viewers alike as Scott’s best performance and film. Don DeFore, Arthur Kennedy and Kristine Miller also star.

Also of interest is 1949’s Easy Living (1949), an intelligent, well-written film about an aging football star, played by Victor Mature, who struggles to adjust to his impending retirement, as well as the pressures brought on by an ambitious and defiant wife (Scott). Lucille Ball is commendable as the sympathetic team secretary and director Jacques Tourneur is first-rate. One of Scott’s finest roles, it is a favorite of many of her fans.

By the end of 1949 Scott appeared in nine films, but did not achieved the level of stardom and clout that was needed to maintain her popularity at the box-office. From 1950 on, she and Hal Wallis passed up numerous opportunities to maintain her stardom. Wallis passed up a chance to star Scott in Lillian Hellman’s Broadway play “Another Part of the Forest” (1946), later to made into the 1948 film. Scott herself passed up the lead in “The Rose Tattoo (19955), a decision she publicly regretted. She continued to make films such as Dark City (1950), Quantrill’s Raiders (1951), Two of a Kind (1951), Scared Stiff (1953) and Bad for Each Other (1953). In February 1954, Scott did not renew her contract with Paramount and became a freelancer. She went on to make the western noir Silver Lode (1954) and The Weapon (1956).

In 1957 she retired from the big screen by starring with Elvis Presley in Loving You (1957), Presley’s second film. Also starring is newcomer Dolores Hart and veteran Wendell Corey. Since 1957 Scott appeared on a few television shows in the 1960s, during which time she attended the University of Southern California. She eventually became involved in real estate projects. Her legacy lives on however in the growing popularity of classic movies sparked by DVDs and movie channels such as AMC (American Movie Classics) and TCM (Turner Classic Movies).