Sondra Locke was born May 28, 1944 as Sandra Louise Smith, probably in Madison, Alabama. She was the daughter of Raymond Smith, a military man stationed nearby, and Pauline Bayne. Smith departed the scene before Sondra’s birth. In 1945, her mother wed William B. Elkins, and together they had a son, Donald, in 1946. The short union ended in divorce. In 1948, Bayne remarried. Alfred Locke bestowed his surname on Pauline’s children and raised the family in Shelbyville, Tennessee, a quiet little town about 60 miles southeast of Nashville. Sondra’s stepfather was a carpenter; her mother worked in a pencil factory. For the smart, fanciful Locke, “My childhood felt as if I had been dropped off at an extended summer camp for which I was waiting to be picked up.” The bright girl loved to read, which puzzled her simple mother, who was always pushing her to spend more time outside. Sondra’s happiest moments occurred on weekend visits to the local movie theater.

Locke was a cheerleader in junior high and graduated valedictorian of Shelbyville Mills’ 1957-1958 eighth grade class. At Shelbyville Central High School, the “classroom was the one place where I felt like I had a chance to prove myself and I continued to excel. I felt safe there and I liked it.” Her best friend was classmate Gordon Anderson. He was a fey young man, who shared many of Sondra’s fanciful hopes about the future and was her collaborator in devising harmless ways to make their lives in Shelbyville more magical. One of the duo’s frequent activities was making home movies with Gordon’s Super 8 camera.

When Gordon attended Middle Tennessee State University (in Murfreesboro, about 30 miles from Nashville) in 1962, Sondra enrolled there too. Upon completing freshman year, Sondra had a blowup with her mother, left home, and did not return to college. Instead, she worked in Nashville as a promotions assistant for WSM-TV, with occasional modeling and voiceover work. She also began acting in community theater as a member of Circle Players Inc. Along the way she dated George Crook, a cameraman from WSM, and Brad Crandall, head of the station’s public relations department. Meanwhile, Gordon revealed to her that he was homosexual. He went off to Manhattan to study acting and, for a while, had a lover there. Anderson was talented but unfocused about his theater craft and eventually returned to Tennessee. Because of Locke’s spiritual kinship with Anderson, she and Gordon decided to wed. The mixed-orientation couple were married at First Presbyterian Church in Nashville on September 25, 1967. (Reputedly, the marriage was never consummated.)

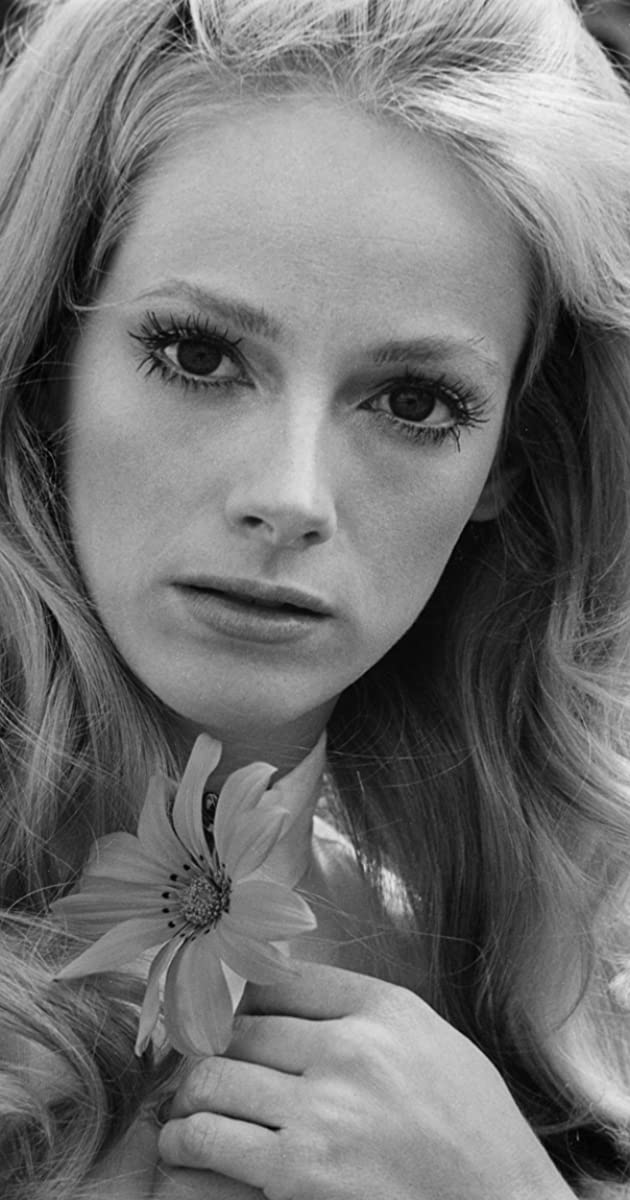

If Gordon was unable to launch his own acting career, he had no such problems igniting Sondra’s. He learned that Warner Bros. was holding a nationwide search for a young actress to play a key role in the screen adaptation of Carson McCullers’ novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1968). Anderson helped Locke research the part of Mick, a teenage waif in a southern town who befriends a suicidal deaf-mute (Alan Arkin) boarding at the house where she lives. For the Birmingham audition, Gordon bleached her eyebrows, bound her bosom and carefully fixed her hair, makeup and outfit so that she would instantly impress casting agents. The ploy worked, and, after several callbacks, Locke — who lied about her age to seem younger — was hired. The movie was released in the summer of 1968 and earned respectful reviews from critics, although many filmgoers found the picture too arty. Sondra was Oscar-nominated for her sensitive portrayal.

Next, Sondra moved to Los Angeles, with Gordon in tow. She hoped to parlay her Academy Award nomination into further movie assignments. The big-eyed, petite, wiry bottle blonde found it difficult to win suitable parts, making her accept lesser projects, the most famous of which was Willard (1971), a film about marauding rats. Cover Me Babe (1970), A Reflection of Fear (1972) and The Second Coming of Suzanne (1974) faded into cinematic obscurity. In the last picture Locke played a Christ figure and had torrid love scenes with Paul Sand. Episodic television provided better acting opportunities: the anthology program Night Gallery (1969) and dramatic series including The F.B.I. (1965), Cannon (1971), Kung Fu (1972) and Barnaby Jones (1973).

For half of the 1970s, the Andersons resided at West Hollywood’s Andalusia condominium complex whilst seeing other people. Sondra was involved with Bruce Davison, her co-star from Willard (1971), and Bo Hopkins, who appeared with her in a teleplay called Gondola (1974). Her fortunes shifted in June 1975, when Warner Bros. offered her the part of Clint Eastwood’s romantic interest in The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). It was a rather minor role, but Locke realized that Eastwood would attract large audiences and thus provide the necessary exposure to revitalize her career. In early October 1975, the pair fell hard for each other on location in Page, Arizona. “We were almost living together from the very first days of the film,” Locke remembered. Besotted Clint confided he’d never been in love before and wrote a poem for his new girlfriend: “She made me monogamous.” This serially philandering megastar was 14 years her senior and a foot taller than she.

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) was indeed a hit, with Sondra sparking a flurry of interest among male viewers as virtually nonspeaking eye candy. Yet she stopped pursuing film roles on her own initiative to assume wifely duties, appearing on the big screen exclusively in Eastwood-controlled projects thereon, with the sole exception of The Shadow of Chikara (1977). (The home invasion thriller Death Game (1977), though released after they became an item, was actually shot in 1974.) “Clint wanted me to work only with him,” she said. “He didn’t like the idea of me being away from him.”

Over the next few years, Locke had two abortions from her relationship with Eastwood. In 1979, she underwent a tubal ligation at UCLA to prevent further pregnancies. She and Clint settled into a $1.12 million, seven-bedroom Spanish-style Bel-Air mansion originally built in 1931, which she spent months renovating and decorating, and which she believed would be hers forever. She continued to spend platonic time with Gordon, whom she never divorced, nurtured by their spiritual relationship. Gordon moved in and out of gay relationships, and sometimes he and a boyfriend would socialize with Clint and Sondra. As for the professional side of things, Locke and Eastwood reteamed for his action opus The Gauntlet (1977), slapstick adventure-comedy Every Which Way but Loose (1978), its sequel Any Which Way You Can (1980), the quirky western satire Bronco Billy (1980) and the fourth, darkest, most ambitious “Dirty Harry” vehicle, Sudden Impact (1983). All were stellar box office performers that cemented the twosome as filmdom’s most visible couple.

During this period, Sondra took a few TV roles when Clint was starring in a movie that had no part for her to play (such as Escape from Alcatraz (1979) or Firefox (1982)). The first time she worked apart from him for any length of time since The Shadow of Chikara (1977) in 1976 was Rosie: The Rosemary Clooney Story (1982). (Rosemary Clooney personally asked Locke to star in the CBS biopic on the strength of her performance in Bronco Billy (1980).) She later made an appearance on Britain’s Tales of the Unexpected (1979) series. For the most part, however, she found herself sitting on the sidelines waiting for Eastwood to cast her in something.

By the mid-1980s, Sondra, over 40, was acutely aware that in Hollywood terms her leading lady days were coming to an end. She had long been interested in film directing and had observed carefully how Eastwood and others directed the pictures she was in. With his blessing, she found a property that intrigued her and that his Malpaso production company would package, and developed it into a project for Warner Bros. She made Ratboy (1986), but despite good reviews, the film received scant distribution. In retrospect, Locke concluded that her exertion of authority over the project caused her longtime paramour to turn away from her, to find someone who was more compliant. (In an unpublicized affair with stewardess Jacelyn Reeves, Eastwood sired two legally fatherless children born in 1986 and 1988, in Monterey — an “evil betrayal” Locke was unaware of.)

The showdown between Sondra and Clint occurred December 29, 1988 at their winter retreat in Sun Valley, Idaho. After an unpleasant screaming match, Eastwood suggested Locke return to Los Angeles without him. She sensed their relationship had passed a point of reconciliation, a fact confirmed when she scarcely saw Eastwood in subsequent months and when industry friends they knew in common shunned her. As she admitted later, “In my head I guess I knew it was over, but in my heart Clint and I were still not severed.” On April 10, 1989, while she was directing a demanding sequence in a new police procedural, Impulse (1990), Eastwood had the locks changed on their house in Bel-Air. He also ordered her possessions to be boxed and put in storage. A letter addressed to “Mrs. Gordon Anderson,” imperatively telling her not to come home, was delivered to her lawful husband’s doorstep. When Gordon telephoned Sondra on the set and read her the letter, she fainted dead away in front of the cast and crew.

On April 26, 1989, Sondra filed a palimony lawsuit against her domestic partner of 14 years. Her “brazenness” in taking on the powerful Eastwood amazed and shocked Tinseltown and titillated the public. Her action sought unspecified damages and an equal division of the property she and Eastwood had acquired during their relationship. Locke asked for title to the Bel-Air home they had shared and to the Crescent Heights (West Hollywood) place Eastwood had purchased in 1982 (in which Gordon lived). The closed hearing was held on May 31, 1989, before a private judge. Before any court decision could be made, a private settlement was reached between the parties. Locke received $450,000, the Crescent Heights property, and a $1.5 million multiyear development-directing pact at Warner Bros. In return, she dropped her suit. By then, the fall of 1990, she was happy to end the hassle. (In the past months she had been diagnosed with cancer, undergone a double mastectomy, and endured chemotherapy.)

For the next three years Locke submitted over 30 projects to Warner Bros., but none received a green light to move ahead. Moreover, the studio refused to assign her to direct any of their in-house projects. In the mid-1990s, Sondra discovered evidence that Eastwood had arranged to reimburse Warner Bros. for her three-year studio contract — a matter that he had never mentioned to her. It became obvious that the studio’s negative professional attitude toward her had little or nothing to do with her directing or project-finding abilities. On June 5, 1995, Locke sued Eastwood again, alleging fraud and breach of fiduciary duty. She claimed that Clint’s behind-the-scene actions had sent a message “to the film industry and the world at large … that Locke was not to be taken seriously.” (According to Sondra’s lawyer, the situation was Clint’s “way of terminating the earlier palimony suit.”)

While Locke’s case was revving up at the Burbank Courthouse, Eastwood begged her to settle. On September 24, 1996 — the morning jurors were set to begin a second day of deliberation — Sondra announced her decision to drop her suit against Clint for an undisclosed monetary reward. One contingency was laid down: she would not reveal the settlement amount. The jubilant plaintiff said, “This was never about money. It was about my fighting for my professional rights.” According to the victor, “I didn’t enjoy it. But sometimes you have to do things you don’t enjoy.” Locke added, “In this business, people get so accustomed to being abused, they just accept the abuse and say, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is.’ Well, it isn’t.”

But Locke was not finished. She had a pending action against Warner Bros. for allegedly harming her career by agreeing to the sham movie-directing deal that Eastwood had purportedly engineered. On May 24, 1999, just as jury selection was beginning, the studio reached an out-of-court settlement with Sondra.

In the decade following her courtroom saga, Sondra did not direct another movie. She did make a brief return to acting with small supporting roles in back-to-back low-budget independent features, The Prophet’s Game (2000) and Clean and Narrow (2000), both of which failed to secure a theatrical release. In 2001, she sold her home in the Hollywood Hills and moved to another part of L.A. After interim flings with producer Hawk Koch and John F. Kennedy’s nephew Robert Shriver, she had a live-in relationship with one of the physicians who had treated her during her cancer siege. Dr. Scott Cunneen, described by Locke as “Herculean,” was 17 years her junior, his mother only three years older than Sondra. She eventually split up with him.

In 2016, preceded by a protracted absence from the public eye, trade press reported that Sondra Locke would come out of retirement to co-star in Alan Rudolph’s Ray Meets Helen (2017) opposite Keith Carradine. The film was booked for a limited run in early spring 2018.

Locke died on November 3, 2018 at age 74 of cardiac arrest stemming from metastatic breast cancer, although it was not publicized until mid-December. The six-week delay raised a lot of eyebrows since the belated news came opening day of the latest Eastwood blockbuster, The Mule (2018). According to a death certificate obtained by the media, her cancer had returned in 2015 and spread to her bones. Locke’s remains were cremated at Westwood Village Mortuary and the ashes entrusted to her husband of 51 years. Rosanna Arquette, Frances Fisher and Evan Rachel Wood were among the celebrities who paid tribute. Despite the acrimony that followed the collapse of her famous relationship, Locke will be long remembered for her prominent roles in some of Eastwood’s most beloved works — and perhaps dichotomously, as a pioneer for the rights of independent working women.