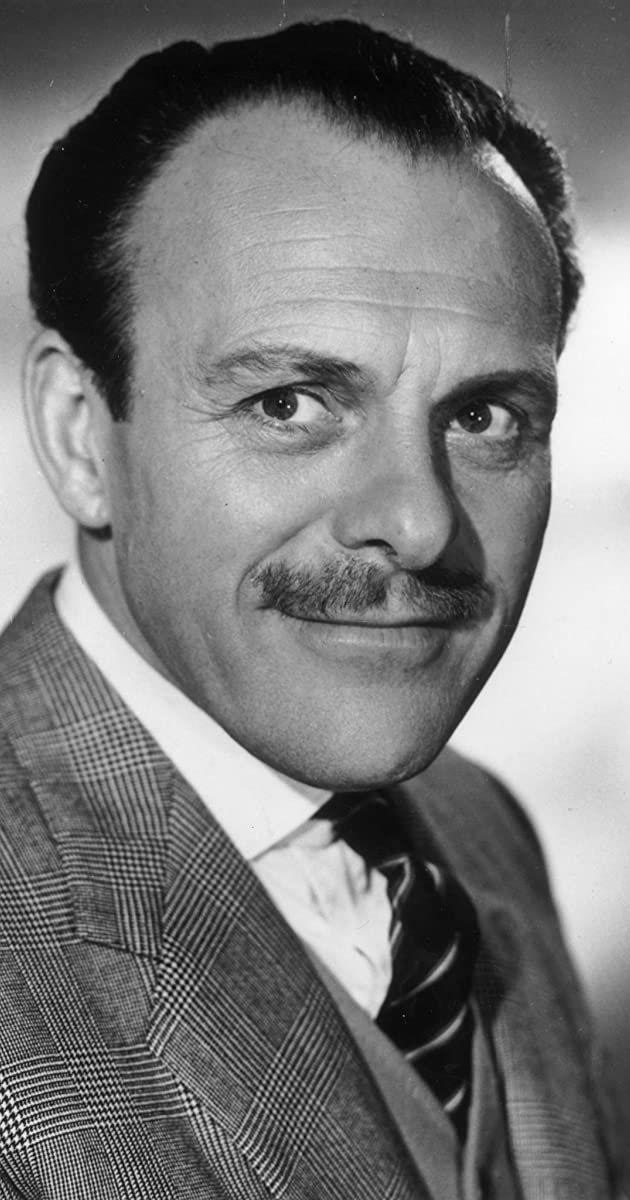

One of Britain’s most beloved eccentric comedians, the irrepressible, gap-toothed Terry-Thomas was born Thomas Terry Hoar-Stevens in Lichfield Grove, Finchley. He was the son of Ellen Elizabeth (Hoar) and Ernest Frederick Stevens, a fairly well-to-do London businessman. He was afforded a private education at Ardingly College in Sussex, with the understanding that this was to lead him towards a prosperous future in the world of commerce. Ironically, deemed to have no acting talent and thus spurned by his school’s dramatic society, young Thomas took to music and soon fronted his own jazz band, “The Rhythm Maniacs”, in which he also played ukulele. His initial experience in the work force was, at best humdrum, at worst traumatic. He started as a transport clerk with the Union Cold Storage Company, went on selling meat at the Smithfield Markets and then peddled insurance policies for Norwich Union. By both choice and inclination, he didn’t fit into any of these jobs, was often bullied and consequently adopted as his life-long mantra the motto “I Shall Not Be Cowed”.

Trying everything to break out of what he perceived as lower middle class mediocrity, he first changed his accent from North London to the posh upper-crust tones of then-matinee idol Owen Nares. He turned to professional ballroom dancing, found work in films as an extra and performed comedy monologues, as well as impersonations in night clubs and cabaret. He also tried several variations for a stage name people would remember, including a reversed spelling of Tom Stevens: ‘Mot Snevets’. Not surprisingly, this didn’t catch on and so he eventually settled on ‘Terry Thomas’, later adding the hyphen, which he likened to the gap between his teeth. His theatrical debut did not eventuate until he was twenty-eight, performing at the Tivoli Theatre in Hull. The onset of World War II put his burgeoning career on hold. He enlisted in the Army Signals Corps and, somehow, rose to the rank of sergeant. Between 1940 and 1942, Terry participated in the ENSA program, staging his own shows “Cabaret Parade” and “Stars in Battledress”. It was at this time, that he first adopted the affected mannerisms, which later became his stock-in-trade. He also demonstrated an amazing repertoire for imitating popular vocalists and for recreating all types of sound effects with his voice.

In July 1946, Terry joined the cast of the revue “Piccadilly Hayride” and suddenly became the comic discovery of the year, which ended with a Royal Variety Performance in front of King and Queen. His proper breakthrough, though, came via his radio show “To Town with Terry” (and its sequel), aired on the BBC Home Service from October 1948. This opened many doors, including Terry getting his own TV series, How Do You View? (1949). He was invited to a cabaret gig at New York’s Waldorf Astoria in 1951. Terry was featured on the inaugural cover of TV Mirror, even before the part of his career he is primarily remembered for had begun in earnest. After a brace of nondescript roles, he was finally cast as the effete, derisive Major Hitchcock in the first of several films produced by the Boulting brothers, Private’s Progress (1956). For several years after, Terry’s popularity flourished with similar films taking a jaundiced view of British institutions. Following his overbearing Bertrand Welch in Lucky Jim (1957), he starred as the titular Carlton-Browne of the F.O. (1959), a satire paralleling the Suez Affair, which turned out to be one of his best roles. Terry played an inept, blundering diplomat appointed as ‘special ambassador’ to sort out the political quagmire of an obscure former colony, overrun by foreign agents and on the verge of an uprising. For this assignment, his character has little more to draw upon, other than his knowledge of Debrett’s Peerage and Sporting Life. This film, established the dandified “jolly good show”-type Terry-Thomas screen personae once and for all.

After Carleton-Browne, came I’m All Right Jack (1959) (in which he recreated his Major Hitchcock character as a representative of management vis-à-vis labour) and School for Scoundrels (1960), in which he was perfectly cast a first-class bounder. Alternating dastardly, moustache-twirling comic villains (Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes (1965)) with sophisticated, rakish bon vivants and impeccably British chauffeurs (Se tutte le donne del mondo… (Operazione Paradiso) (1966) or butlers (How to Murder Your Wife (1965), popularised Terry on both sides of the Atlantic. Mostly, he came to epitomise the archetypal British ‘silly ass’ — an instantly recognisable figure replete with RAF-style moustache, cheeky gap-toothed grin, mobile eyebrows, flashy waistcoats, button-hole carnation, suede shoes and enormous cigarette holders (including one studded with 42 diamonds!). Life imitated art, when it came to womanising, clothing and accessories. Terry, a founding member of the London Waistcoat Club, ended up owning more than 150 of these garments, in addition to 80 Savile Row bespoke suits.

In the late 1960’s, Terry settled on the island of Ibiza with his twenty-six year old second wife. However, by 1984, his prior extravagant lifestyle and the exorbitant costs associated with the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, with which he had been diagnosed in 1971, forced the couple to sell the villa and move back to a sparse flat in Britain. Almost destitute, his remaining days were made easier by his numerous friends in show business who managed to raise 51,000 pounds for him at a London benefit. Terry-Thomas died at a high care nursing home in Godalming, Surrey, in January 1990 at the age of 78.